“… Look at it this way: you’re getting 10 for the price of three!”

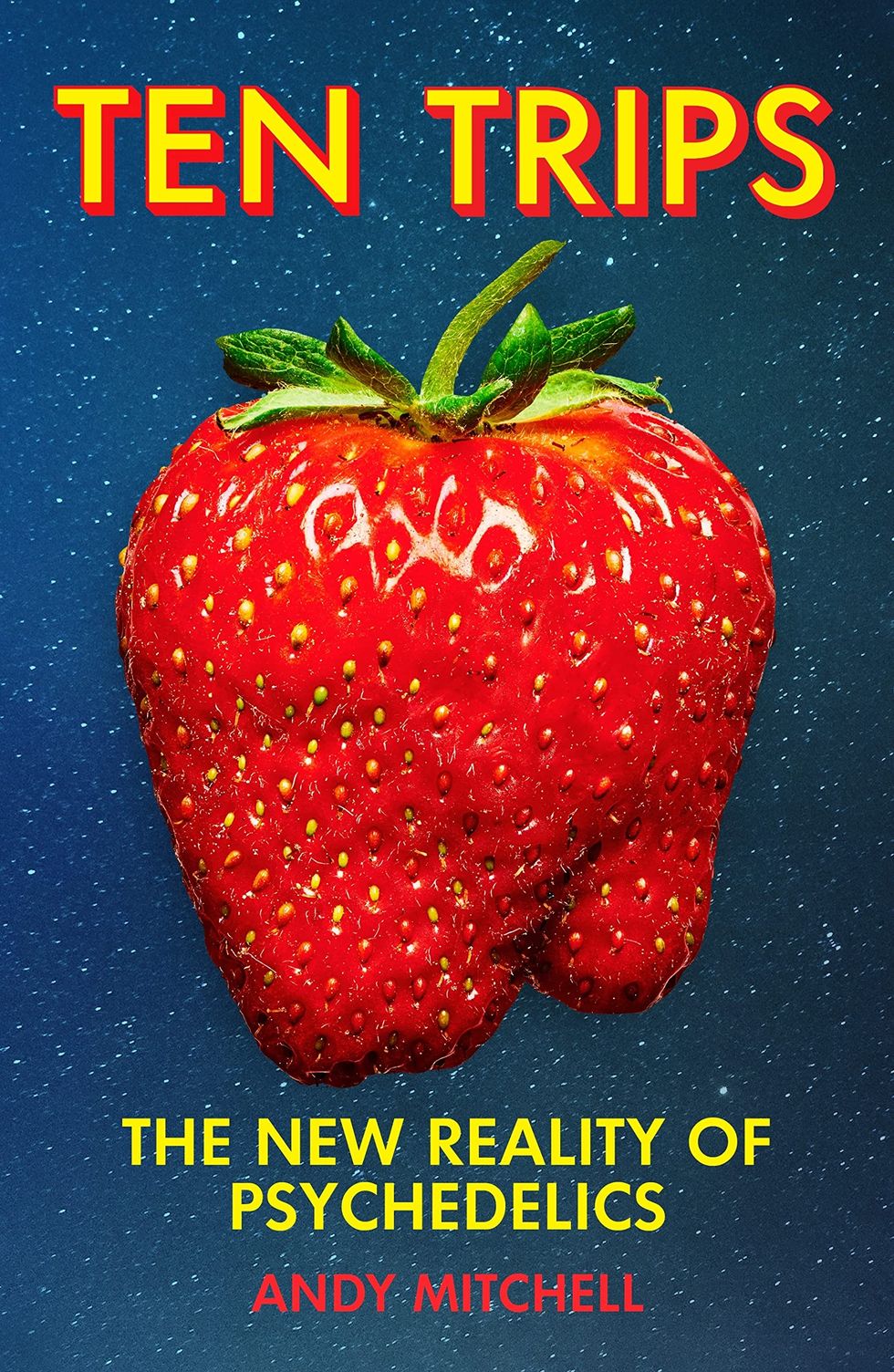

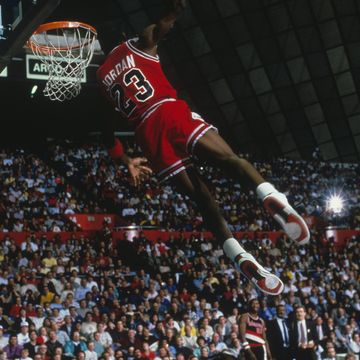

So ended the elevator pitch for my new book Ten Trips: The New Reality of Psychedelics, the 10 that I experienced trumping the three that esteemed American author Michael Pollan took in his 2018 best-seller How to Change Your Mind. As engaging and culture-shaping as Pollan’s book was, its concerns – championing the medical use of psychedelics as a treatment for mental health disorders – were relatively narrow, its tone straightlaced, to ensure as broad an appeal as possible given the sticky business of mass drug-taking.

Five years on and the psychedelic hype is such that we have launched a “new era in psychiatric treatment” according to a recent NPR programme. Venture capital funds have created multiple international start-ups, such as COMPASS Pathways and Atai Life Sciences, that compete with traditional Big Pharma to develop and patent variants of psychedelic drugs and therapeutic protocols to sell to healthcare providers for widespread medical use. In the US alone the projected value of the magic mushroom market in 2028 is $6.4 billion, which puts it on a par with that for baby food, and nearly 10 times that of M&M’s. What was, for decades, marginal, has once again become of interest to the ordinary and extraordinary alike: in March 2023, Gabor Maté, the well-known physician and author specialising in trauma and addiction, interviewed and diagnosed Prince Harry on television, following the Royal’s astonishing, transformative experiences with a psychedelic tea.

Five years of cultural mainlining, of macro-investing and microdosing, of candy-flipping and seven-star retreat centres, all promising “ego-death”, “connectedness”, “eco-consciousness”, “cognitive enhancement” and “net-zero trauma”; five years, that is, of the so-called Michael Pollan Effect – and the psychedelic field is neither narrow nor straightlaced anymore. These days that field looks like a cross between a Disneyfied theme park and the death throes of an international rave: vast, expensive, over-trodden, lacking signage, and with more than a few people looking worse for wear (it turns out that some are traumatised rather than cured by the drugs). Five years on from Pollan, the psychedelic conversation needs broadening, updating, messing up a little: we need to know how to change our minds all over again.

My aim was to plot a course map of the entire psychedelic territory, and a purge bucket for the hype. For Ten Trips, I took 10 different substances in 10 different contexts: DMT in a neuro-imaging research trial, magic mushrooms on a therapist’s couch, ayahuasca on the altar of a psychedelic church, LSD on the roundabout of a dual carriageway, mescaline half-way up Half-Dome, iboga at a plant-based retreat centre in the Bahamas, vaporised toad venom in some forest above Silicon Valley, and eventually, inexorably, to the indigenous cultures of Mexico, Peru and Columbia that have used the medicines for aeons: as someone sagely told me, with psychedelics, all roads eventually lead South.

It turns out the territory looks very different depending on who’s looking at it. Where neuroscientific research looks for drug-induced changes in patterns of connectivity in the brain – “neuroplasticity” is the technical term – psychedelic-assisted therapy sees changes in “psychological flexibility” in the mind. Are plasticity and flexibility the same thing? Similar even? Or strangers separated by a philosophical abyss? Are they the same as “awakening” in psychedelic churches, or the “healing of our animal spirits” the shamans look for when they drink the medicine on our behalf? Presumably all were very different from the humbler, more down-to-earth claims of “recreational” users, like “getting off our heads,” which seems to be at an equal distance between pleasure, relief and play. Meanwhile, on the ground beneath their feet, the vines, the mushrooms, the cactus and the toads couldn’t care less.

It’s now several months after I finished my drug odyssey. Give or take a few days of patchy memory, mental tyres spinning in snow, the mind I have is recognisably the same as the one I left with. Psychedelics are the epitome of TMI, meaning there’s a trade-off between, on the one hand, the most intensely enchanted nights of my life, of astonishing transformations, of new friends, of love abounding; and on the other, the sense of extraordinary experiences piling up on top of one another to the point where they consumed each other’s meaningfulness.

My mental health and personality are more or less the same inconsistent soup they were before, though there have been subtle, significant changes in their flavour. I’m more aware of that part of me that always needs to run – towards the wrong thing, away from the right thing. I have new (infrequent but regular) urges and desires: to wear kaftans, to do my own plumbing, to work in hospice care. One definite change: after years of threatening to write, there’s finally been a demonstrable shift in my creative output, this book being one piece of material evidence (some of it was written while micro-dosing with LSD, other bits on mushrooms; maybe the discerning reader will be able to tell).

At the outset of the book, I adopted the metaphor of the multifaceted gem for the different aspects of psychedelics; the way that medical models for usage, competed with religious-spiritual ones, while both of them treated recreational usage with disdain. But I’ve outgrown this metaphor, or better to say, psychedelics have slipped its net. A jewel is man-made, but the most fundamental lesson of my various trips is that these drugs defy our attempts to model them while showing us something of what we want to see; a self-portrait perhaps, only in a convex mirror (to borrow the title of a John Ashbery poem). Implicit in the jewel metaphor is the idea of a single definite form (albeit with myriad facets), and I’m not convinced that suits psychedelics.

Water, though, has no such form. While we might know its chemistry, or the behaviour of its molecules at different temperatures – the science of water, in other words – at the level of experience it’s a substance that takes the shape of whatever contains it, while being impossible to observe without some container. I’ve come to think of our psychedelic journeys in a similar way, as being like water. Whether we’ve got a mental health diagnosis or believe we have trans-human potential, whether we’re tripping in a therapeutic “living room”, a Caribbean retreat or a maloca on an Andean mountain-top, whether we have embarked with a very specific intention, or no intention at all, whether we are accompanied by a Bach Mass, a Shipibo icaro or “Strawberry Fields Forever”, the water – the journey, that is – just keeps on changing form, bringing our lives to life in unfathomable ways, including all that we are, which is far more than we know.

'Ten Trips: The New Reality of Psychedelics' by Andy Mitchell is out on 21 September (Bodley Head)