When I was 17, I got a girlfriend. The relationship divided my four older siblings along two lines: some who felt I was too young and would be corrupted by it, and those who thought it worthwhile. In the first camp were two of my older brothers, and in the second, my sister, and my oldest brother who saw himself as a philanderer. He’d had his first sex around that age and saw in my move a manliness that aped his own, especially because my girlfriend was considered by most of the boys who lived in our gated estate to be a great beauty.

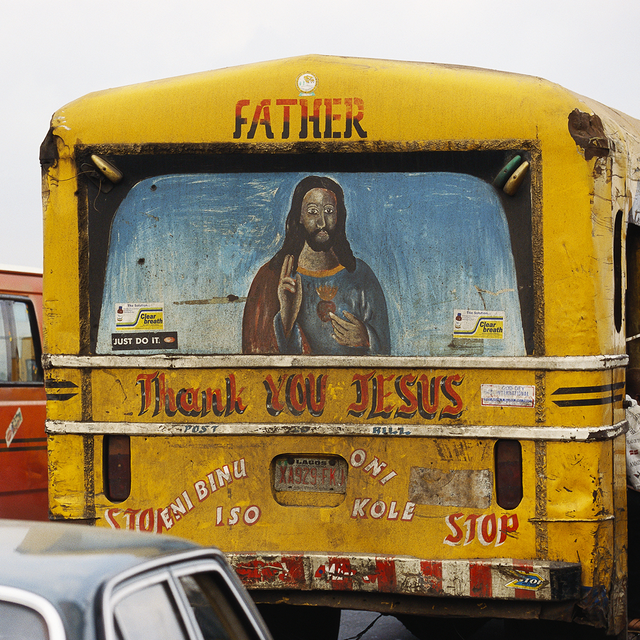

The sibling to whom I was closest at the time, Joseph, was in the first camp, however. His objection stemmed mostly from his religious devotion to pre-marital celibacy. Like most southern Nigerian families, we were devout Christians. When he saw that I would not break off the sinful union, he withdrew from me.

To draw Joseph back to me, I decided to join the group in the church with which he was most involved. The evangelism group of the church consisted of the most devout. They went out every Saturday evening to take the gospel to the doorsteps of the unsaved, knocking on doors and standing on street corners. Even though we had not had sex — my girlfriend was a Muslim who wanted to have sex only after marriage — I felt indelibly stained by the kissing and humping we did behind the stairs of my side of the estate and in other covert spaces. I hoped my brother would see that though I had a girlfriend, I was still a believer.

I found the task of street evangelism to be daring at first. We were speaking to strangers, knocking on the doors of unknown people. There were those who sought our message, children who danced to our singing, aided by tambourines and flutes, those whom we met at their broken moments, who sank to their knees at our approach, desiring our message. Once, we knocked on the door of a woman who listened to us with tears in her eyes. She confessed that the man whose voice we’d heard within the house was not her husband, but one who visited while her husband was away.

We preached once to a man who sobbed with a great, wasting lamentation. He confessed to being haunted by the guilt of a murder he’d committed. “I killed him with my own bare hands,” he kept saying. But there were those who saw us as a nuisance and slammed their doors on our faces.

Once, a sister decided to preach to two men crouched under a tree near the Makurdi stadium, smoking ganja. When the sister began to speak, one of the men mumbled something over a whiff of airborne smoke, that he did not care about Christ. But the sister had seen this as an encouragement to continue. The man sat still, his dry, chapped lips pursed in some kind of discombobulated restraint for some time. Then he stood suddenly and gave the sister a wide slap across the face. We fled.

One evening, two months into my joining, we ventured far out into Makurdi city, preaching and singing. We stood at the junction near the iconic statue of the food basket on the roundabout’s centre island. We’d been preaching here for about an hour and 30 minutes or more when, across the junction, a lady walked up to me and another brother. We’d seen her earlier and the brother had tried to speak to her, but she’d merely hissed and walked past him. A relentless proselytizer, the brother had followed her, riffling between other commuters, hawkers bearing their wares on trays balanced on their heads, until he managed to slip her a tract a few hundred yards away.

Now, the woman came up to us with the tract in her hands, its pages creased and stained by sweaty dirt.

“You… came back, ma,” the brother said, not knowing what to do in this situation. We were itinerant preachers: we walked to you, gave you the gospel and walked away or you walked away. We did not expect you to return.

“Yes,” she said, almost with calculated reluctance.

“Praise God!”

The woman nodded.

“Welcome, ma,” I said.

She nodded again and I looked up at her eyes and saw a trail of tear slide gently down. She wiped her eyes with the back of her hand. As she did, I could see the tract the brother had given her was the one with the title “Repentance” written in bold blue ink, followed by the question: “What is the biggest decision you’ve ever made?”

“I want to just tell you… I want to just say.” She sobbed now, lifting the tract toward us.

The traffic was jammed, causing irate drivers to honk and shout so much we could barely hear her. She learned toward me and whispered in my ears, “Can we go over there — look, at that road there? I want to tell you people something.” I shouted the message out loud to the brother and without a pause, he gestured to the others that we will be back.

The woman led us to a quiet inner street with an unpaved road patterned by litter, long sutured into the earth by car wheels and shoes. We stopped near a lone tree in front of a gated building, and when she’d caught her breath, she said, “My brothers, listen to my story.” I saw, now, that she was no longer crying.

She’d passed us earlier on the way to a house on a street nearby. There she’d hoped to find the man who had treated her very badly, cheated her of all her life’s savings and disappeared to live there with his paramour — a girl she’d once employed at the hair salon. She had come out that evening, to kill both of them and herself.

Before I could make full sense of what she’d just said, she looked around about her as if to make sure no one else but us three were there. Then, gesturing that we step forward, she opened her handbag. I peered into it, and between pieces of naira notes, a comb and other effects, was the stock of a black pistol.

“It is real,” she said, now in whispers, as if she could see the jump in my heartbeat. “Touch it — put your hand inside and touch it.”

I touched it after the brother, it was heavy and cold.

“I would have killed a person today — this evening,” she said now with renewed surge of emotion. “But when I read the first words of the tract, it touched me. It touched me because I was afraid already. After I see maybe it is not worth it again. If I kill him now — if I kill her self — what did I gain?”

She fell silent now and it seemed she asked us this question. So, I said, “Nothing, ma.”

She nodded. “Nothing,” she said, and the tears filled her eyes as if something in them had suddenly ruptured.

She kept saying the word as she walked away, back in the direction from which she’d come, her shoulders heaving. We stood there, the brother and I, gazing after her unsure of what to make of what we’d just witnessed.

I returned home that night aware that this thing I was doing to earn my brother’s grace, had produced a result way beyond its spiritual intention. I knew I had experienced something which, although occasioned by chance, would always remain with me. If I choose to, I see her face still.

Chigozie Obioma is the author of the novels The Fishermen and An Orchestra of Minorities, both of which were shortlisted for the Booker Prize