On 22 February 2019, a new restaurant, Gloria, opened halfway down Great Eastern Street in London’s Shoreditch. To describe it as “highly anticipated” would not be accurate. Not only was there little to suggest that Gloria would be successful or popular or good, there were hints that it could be an epic, of-the-ages case study of wrong place, wrong time.

The location was great — in 2012. Now the kids had moved further east or south, and the crowd in Shoreditch is what New Yorkers would call “bridge-and-tunnel”. Gloria’s parents were Victor Lugger and Tigrane Seydoux, also known as Big Mamma. They are French but Gloria would be exuberantly Italian: Italian food, bought direct from small-scale Italian producers, served by Italian staff. These are confounding times to be a cosmopolitan, Euro-leaning business in Britain; you might have noticed, but Lugger and Seydoux didn’t seem to. And Gloria would be aimed at the mid-market: an unforgiving, overcrowded sector with paper-thin margins, especially if you’re serving pizza and pasta. Ask Jamie Oliver or Pizza Express.

Lugger and Seydoux wanted to throw a party to celebrate the launch of Gloria, but their public relations advisors weren’t sure. It would cost a fortune to fill the restaurant, a sprawling 160-cover site spread over a ground floor and cavernous basement, and you couldn’t be sure of much publicity from it. Serious reviewers, for certain, would have to come back another time. Lugger and Seydoux, 35 and 34 respectively, chose to ignore them. The clue is in their name: Big Mamma. The group has six relentlessly busy restaurants in Paris, as well as overseeing La Felicità food market in the 13th arrondissement, which seats more than 1,000 people in Europe’s biggest restaurant space. On Gloria’s opening night, they stockpiled bottles of limoncello like they were expecting the apocalypse and planned to drink through it. The word “Brexitalia” was hastily sprayed on what looked like a bedsheet and hung over the front door. It might as well have read, “Fuck you.”

Nine months later, we are still talking about Gloria. On its first day, a Friday, a long queue snaked round the building. They served 600 diners. Day two: 700. Within four weeks, Gloria was at absolute capacity: a near-mythical state for restaurants that, even if doing improbably well, might take six months or more likely two years to attain. It would be almost unprecedented, except for the fact it has happened to the Mamma boys a few times now. Their ability to open a new restaurant, pack it and keep it packed makes them, at least in London in 2019, something close to alchemists.

Not that they see it that way. “So the first day you have 600 people and, since it’s not our first restaurant and I think we know what we’re doing, people had a good time,” says Lugger, over lunch at Gloria. “These people each tell 10 people: ‘I had the most amazing dinner in that new restaurant’. So the next day there is 6,000 wanting to come. The next day there is 60,000. And the next day 600,000. By the end of the week there’s five million people who know about your restaurant. That’s how fast it goes.”

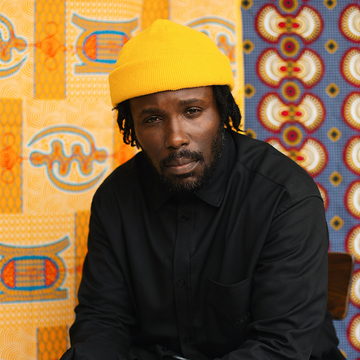

Lugger wears thick-rimmed, round spectacles, and a fitted, black roll-neck, just in case anyone wasn’t sure he was French. He first learned English when he was packed off to Gordonstoun boarding school in Scotland for a term when he was a teenager — “I was a real piece of shit and it did me a lot of good to come here and be a little bit bullied by all of the kids” — and moved to London two years ago with his family when the Big Mamma group was preparing to open Gloria. He goes on, “People love to talk about movies they’ve seen and restaurants they’ve been in, and slightly later they talk about their kids. Period.”

Not long after opening, the reviews landed. These can be collated as: “I thought I’d hate Gloria, but…” Because there’s much aesthetically and gastronomically you might take issue with. The restaurant was designed by Lugger and Seydoux with a declared aim to recreate Capri in the Seventies: gaudy velour booths, lampshades with frilly fringes, a jungle of plants and preposterously large laminated menus. The music jumps from opera to Euro bangers like you’ve got an old man and a teenage girl in a car passive-aggressively arguing over radio stations. Even the loos are a talking point: the cubicle doors (the women’s, not the men’s) are fitted with two-way mirrors.

But it is the food that is perhaps the most un-2019 thing about Gloria. There is no auteur chef behind the project, only indulgent, high-cal Italian-ish staples often with groan-inducing titles. There’s Filippo’s Spicy Balls, meatballs made from slow-cooked pork and nduja; carbonara is served in a giant wheel of pecorino; pizza options include the Robert de Nitro. Nothing about this place isn’t a bit cheesy.

Then, this summer, Big Mamma opened a second London site, a temple of Bacchanalia that made Gloria look prim and reserved. Football-pitch big, Circolo Popolare could fit 280 diners at one time. Its location, off Oxford Street in Fitzrovia, was a bit odd, but, as Lugger says, “We immediately saw we can do a fuck-off restaurant here”. The puns were perhaps even worse — who ordered the I Wanna ’Nduja? — and on the walls were 20,000 bottles of booze, an idea Lugger took from a restaurant in rural Italy. “I spend my life in restaurants and I can tell you there are not many things you can put on a wall that look good,” he says. “There is a window, there are frames, there are bottles. That’s pretty much it.” Besides, that other restaurant only had about 50 bottles on its wall. “So when we steal an idea from someone or from so many people, at least we try to do it with panache — would you say ‘panache’ in English?”

Circolo Popolare didn’t quite match the buzz of Gloria, but in any other year, it would have been a stand-out London opening. Articles now proliferated attempting to explain why, when everyone else in the restaurant industry was finding life hard, Big Mamma made it look so easy. The Sunday Times’ Marina O’Loughlin asked, “Have the owners created something completely, perhaps slightly alarmingly new, verging on the subversive? Could this be the first upscale restaurant where the food is irrelevant? Because this bunch don’t open restaurants to feed people or win culinary awards, but as all-caps EVENTS.”

Elsewhere, Big Mamma’s popularity was put down to the need for escapism in the Brexit age or millennials seeking out cut-price experiences or the power of Instagram in disseminating cool. I put these theories to Lugger: which does he think is most important? “In my opinion, which is very personal and with zero hindsight, because it’s my company and I work like 13 hours in these restaurants for six years, all that is…” he pauses, carefully choosing the word, “over-rationalising. Yes, you can say it’s because of Instagram, millennials, the perfect alignment of planets, but I feel there are many things here that are ephemera.”

So what is it then? “We have been doing this for four-and-a-half years and every day, with no exception, we have more clients in every one of our restaurants,” he says. “The success, I believe, is due to four things: it’s good, cheap, served with a smile, [and] in a nice restaurant. The second any of our restaurants stop delivering this, it’s going to stop being successful. And the second it starts doing this again, it’s going to be successful. Every restaurant in the fucking world, and I can open another one here and another one here” — Lugger gestures out of the windows of Gloria — “if they are good, cheap, service with a smile and nice design, they will be packed. That is the reason for the success.”

Eating lunch with Lugger is fun but not exactly restful. He is convivial, entertaining company: wry, generous and very, very opinionated. But his brain is always whirring, taking in everything around him. “This is my job: I see,” he says, and both he and Seydoux try to eat at their restaurants eight to 10 times a week. “Right now, I’ve seen 20 problems that happen today at lunch. It’s just that they are small problems so they are fine.”

For example? Lugger points to a man at a table over my left shoulder. He’s alone, waiting for his companion to come back from the loos and looks to me like he’s wondering if he has enough time to check his phone, but not be caught. Lugger sees something different. “He’s waiting for his food and now it’s probably been two minutes too long,” he says. “He’s starting to think it’s too long. I’m thinking, ‘OK, it’s too long, why?’ I’m going to see what he gets as a dish and maybe I know this dish takes a long time and I’ll say, ‘It’s fine, I knew it when we conceived it, but this dish is so amazing it will offset his anger or anxiety’. But if it’s a burrata and it takes too long, we are just fucking up. And at the end he will maybe not write a review, when on the contrary if it had come faster he would have written a five-star review.”

Seydoux, meanwhile, whom I had met alone a couple of weeks earlier (Lugger had been ill), is more measured, less bombastic. He, too, is handsome, with a big sweep of chestnut hair and pale skin that reminds you of Léa, his Bond girl cousin. Seydoux has stayed living in Paris, ostensibly looking after the French interests for Big Mamma, but in truth he and Lugger are inseparable, taking all decisions together. Broadly speaking, Seydoux does people and Lugger does food, but you notice after you’ve spoken to both that there is nothing substantive they don’t agree on.

They met at a business school, a prestigious grande école called HEC Paris that has been turning out French politicians and intellectuals since 1881. At the time, Lugger was a music producer and Seydoux worked for one of France’s most successful entrepreneurs, but quickly they were pulled towards doing restaurants. Seydoux had a background in hospitality (his father, Jacques, managed ultra-deluxe hotels in Monaco and Paris) while Lugger was obsessive about food. Their first decision was what their places would serve. “Quite fast we went to the Italian cuisine because we love the food,” says Seydoux. “Stupid, but it’s the first reason.”

Next came the business model. Most restaurateurs, Lugger and Seydoux started to believe, fixated on margins when what’s really important is volume. In other words, if your place is full you will make money. “It’s very simple, the restaurant industry,” explains Lugger. “If there is a queue or a waiting list, the restaurant turns profit 99 per cent of the time. If it’s empty or half-empty it’s not working. It’s simple maths.”

Lugger and Seydoux were drawn to large sites: they were the riskiest but offered the greatest rewards. They would need to be in a decent neighbourhood, but not the prime spot. Now, how to control food costs and guarantee quality? They decided the only way was to work directly with producers in Italy. For a year-and-a-half, Lugger and Seydoux went back and forth, up and down the country meeting farmers. “We were going to Italy for a month, renting a car, it was quite nice!” recalls Seydoux. At the end, Big Mamma had struck deals with around 180 of them, cutting out middlemen.

This might all sound a bit technical, but this early groundwork is crucial to the experience of going to any Big Mamma restaurant. Say it again: good, cheap, service with a smile, and in a nice place. Eating at Gloria feels luxurious, even decadent. Their best-selling dish is twisty ribbons of fresh mafalda pasta with mascarpone and a shower of black Molise truffle, for £18. There’s a joke that every dish comes with burrata, mozzarella’s fancy cream-and-curd-laced cousin, and half a dozen do. Yet the average spend in Gloria is around £25 per head. (Here’s another way in which Lugger and Seydoux are smart. Black truffle might seem indulgent, but it costs a fraction of the price of white truffle: “In Umbria, truffle pasta is their tomato pasta,” says Lugger. He would love to have, for example, turbot on the menu, but it would be far too expensive for the price points they want to hit.)

“I enjoy having in my restaurant a billionaire from Abu Dhabi who is staying at Chiltern Firehouse and comes here on a Saturday evening and buys a £500 bottle of wine,” says Lugger. “But we also have the workers from next door that come for a pizza. And the single mother with five kids on brunch and the foodie blogger and the girls from the bank next door. Everyone.”

I don’t know how many workers from the building site across the road I saw in Gloria, but it’s true that it does attract an unexpectedly diverse crowd. If you want to eat with, to pluck two recent sightings at random, Alexa Chung or David Schwimmer in London’s most-talked-about restaurant, you just have to queue, like anyone else. Good, cheap, service with a smile, in a nice place: it all starts to feel transgressively democratic.

When Big Mamma was starting out in Paris in 2015, Seydoux liked to call his restaurants “antidepressants”. And it’s a perfect description. I’ve eaten some memorably excellent food at Gloria and Circolo Popolare — that truffle pasta; mind-blowing tiramisu — some soporific, claggy things, but I’ve never left there without a bounce in my step (apart from the time I had a massive row with my girlfriend in Circolo, but it seems unfair to blame that on Lugger and Seydoux). Perhaps it’s the house limoncello they finish the meal with, whether you want it or not, but there’s also the flirty waiters and a sense of geniality and warmth that does make you feel like you are on holiday, or certainly not in Britain.

“There are many restaurants where it’s going to be challenging and you’re going to learn a lot about life and about yourself,” says Lugger. “That’s not what we do. We are a trip in Italy. It’s probably going to be warm and everyone is going to be nice, the sun is going to shine and there is going to be a lot of atmosphere. You’re going to get drunk and smile and laugh and eat generous, tasty food along the way. That’s what we do.

“So I’m the biggest competitor to Ryanair. Don’t write that, it’s stupid” — sorry Victor — “but that is my analysis. It’s not just millennials that want cheap, good food; everyone wants good value for money! Not just millennials.”

In so many respects, Gloria and Circolo Popolare are the perfect restaurants for the Instagram age. The plates and bowls are hand-painted in eye-popping colours in ceramic workshops in Deruta, Umbria. Serious money has been spent on the interiors and then styled to look like it hasn’t been. “Look at this fabric,” says Lugger, running his fingers over the banquette on which we are sitting, which has vertical stripes of red and blue. “This looks very ugly in a small sample. You would see that and not put that in your home. It’s ugly-beautiful, but if you know Italy, you can say that’s something you could find in Italy. Creating authenticity — of course, it’s a contradiction in itself — is the hardest and funnest and greatest part of our job.”

Partly the restaurants’ designs reflect Lugger and Seydoux’s personal taste. “We’re definitely not minimalist people,” says Seydoux. “We’re not Swedish.” They are also self-aware enough to know a restaurant needs a strong visual identity. But they insist it is not connected to Instagram (neither man has a personal account, though Big Mamma has 180,000 followers) and are adamant they have never spoken to consultants to make their dishes more photogenic. “We try to build restaurants and cook dishes that taste good, smell good and look good,” says Lugger. “You can be as smart as you want, but if you never wash your teeth, it’s going to be hard for you to hook up with a girl. Same with food. It has to taste good, smell good and look good, and if you do that, it will end up on Instagram.”

How long Gloria will reign in London, you wouldn’t like to guess. Nowhere was hotter than the Polpo restaurants five or six years ago, but this year, as debts mounted, multiple sites closed. What makes Big Mamma think it will be any different for Gloria and Circolo Popolare? What happens when trends in food change? “No! I totally disagree,” exclaims Lugger. “Trends in food don’t change. Maybe you’ll think, ‘Oh there’s a new trend: al pastor tacos…’. I love al pastor tacos; I could feed myself with Indian food and al pastor tacos, to be honest. But it’s not a big thing. No one gives a shit about al pastor tacos apart from the three small restaurants that cook them and the press because they have to come up with new things.

“People,” he goes on, “are still eating pizza, burgers, classic British food, classic French food. And, well, two-thirds of the world are eating Indian and Chinese food and some sushi. That has not changed a lot for a very, very, very long time. We can have an appointment for 10 years when maybe we fail and people ask me, ‘Why?’ Then I hope I will not tell you, ‘Oh, it’s because trends changed’. Please! In 10 years, people will still be eating Italian food. If in 10 years or tomorrow morning we fail, it’s because we are not achieving quality and consistency. And as long as we do I am very confident that we are going to fill as many restaurants as we have.”

Good. Cheap. Service with a smile. Nice place. Can it really be that simple? As the limoncellos arrive, Lugger is clear-eyed that the formula is irresistible. In 2020, Big Mamma will open its first restaurant in Spain, with Seydoux moving his family to Madrid to oversee it. They have looked at more sites in London, but they weren’t quite right. “The restaurant business is both threatening and reassuring,” concludes Lugger. “It’s threatening because it’s a job that starts again every lunchtime, every dinner. But it’s very reassuring because it’s all on our shoulders. If we do our job, it’s going to work.