If one dish sums up the ethos of Danish chef Rasmus Munk’s Copenhagen restaurant, Alchemist, it’s one he calls “Food for Thought”. Instead of on a plate, “Food for Thought” arrives in a silicon replica of a human head, from which the skull cap is lifted off at the table revealing a square of pâté de foie gras in a Madeira casing, topped with a square of pale, aerated foie gras that has the texture of dried lichen. The foie gras is from Spain, “ethically” produced from geese that are not force-fed. It is thought-provoking, it tastes like nothing you’ve ever had before, and it’s also completely, delightfully, batshit.

“What’s in fashion in the culinary world I would say is to cook less courses, more family sharing things, and only focus on good ingredients and seasonality,” says the 28-year-old Munk, a few hours before the evening’s service begins. He’s sitting on a velour sofa in the lounge area of Alchemist, which is inside a gigantic shipbuilding warehouse once used as a backdrops store by the Danish National Theatre. To Munk’s right is a three-storey wine cellar that holds 10,000 bottles which he designed himself. Facing him is a glass window through which chefs can be seen going about their prep in the test kitchen. One of them appears to be using a drill.

Alchemist opened in July to considerable fanfare: in a city whose culinary scene is dominated by the likes of Relæ, Geranium, Amass and, of course, René Redzepi’s Noma, Alchemist is unashamedly molecular and maximalist. This is dinner as promenade theatre, with guests invited to move around the building for different stages of their meal, which is divided into “acts”. Most of the courses are served in a dining room with a domed ceiling onto which a series of slowly changing images is projected — of tree tops, falling stars, jellyfish, plastic bags — to a background of slow, surging synth chords.

Most mind-bending — and waistline- expanding — of all, the menu runs to 50 snack-sized courses, or to use Munk’s terminology, “impressions” (only 46 are actually edible; a further four are experiences). Dinner lasts around six hours. “It should be like a filmic experience to be here,” says Munk. “You should forget about time and space when you walk into this restaurant.” Given that a meal with the entry-level wine pairing costs around £500 a person, you might want to forget about your bank balance, too.

For all the theatrics of his venture, Munk is surprisingly understated: softly spoken, red hair, black jeans and a black T-shirt revealing arms covered in tattoos. On his left forearm he has trees typical of the woods near where he grew up in Randers, Jutland; on his right he has edible herbs and a quote from chef Thomas Keller, of California’s The French Laundry: “Respect for food is respect for life”. When we meet, Alchemist has been open for a week, during which Munk has been pulling 20-hour shifts. “I’ve slept here once,” he admits, though he doesn’t feel too exhausted. “More nervous I think. We’ve had some good reviews already, but I’m still a little bit anxious about the future.” (He needn’t be overly worried: at the time of writing, the restaurant is fully booked until the end of September, with an estimated 5,000 people on the waiting list.)

Even though Munk has been cooking since he was 14, it was not an obvious career for him; perverse, even, given that his family, he says, has a tradition of culinary ineptitude. “My mother is a terrible chef, my grandmother is a terrible chef,” he says. The family’s priorities were “a nice roof on the house and a nice car in the garage”; they went to McDonald’s every Friday.

Munk himself was “a really lazy young guy that was only doing bicycles and scooters”, but he followed a friend to culinary school “because you could get some money from the government” and found it transformative. “I remember it very clearly: we should make a dish with carrots and chicken. There was around 20 students, and I just thought this teacher must have the most horrible job in the world to get 20 times overcooked carrots and boiled chicken, without any salt or butter. I just thought there’s so many things I don’t know about it, and that turned me on a lot.”

His sharp learning curve took him from a catering company to stages at various restaurants including Noma and The Fat Duck in Bray, to head chef at an upmarket Danish hotel. Not surprisingly, he cites Heston Blumenthal and El Bulli’s Ferran Adrià as influences. “Their version of molecular cuisine showcased that you can do something more than just great food on a plate: you can also tell a story behind it, and that’s been a huge inspiration for me. I think chefs right now have so much attention in what they’re doing, so you have a responsibility to do something more than just cooking a great meal.”

In 2015, when Munk was only 24, he opened the first iteration of Alchemist: a 15-seat restaurant in northeast Copenhagen. It earned him a reputation for attention-grabbing, message-serving dishes — one was a bowl of live woodlice to be doused in tom yum broth and transformed into tiny crustacean croutons, to highlight the use of insects as a viable food; another looked like an overflowing ashtray but was actually made from bacon, onion and potatoes — a tribute to Munk’s grandmother, who died of lung cancer.

One evening, a couple of months after opening, he was visited by Lars Seier Christensen, co-founder of Saxo Bank, who liked what he saw and ate and offered to invest. “I was like, ‘No, I don’t want anybody to invest now, things are fine for me’,” says Munk. But Christensen, who also owns the three-Michelin-starred Geranium, persisted. “He was like, ‘OK, tell me your dream’,” remembers Munk. “I did a lot of sketches, and I was like, ‘This he will never buy because it will cost millions to build’. Surprisingly enough he said it sounded amazing and it didn’t scare him.”

While the original Alchemist, which closed in 2017, occupied 100sq m and employed six staff, the new Alchemist has 2,000sq m and nearly 50 staff. Even when costs spiralled — hitting £15m, 10 times the original budget — Christensen coughed up. “But it’s been tough! You can mention that,” says Munk. “He has some very sharp lawyers and accountants and I’ve been struggling a lot, but it’s part of the game. It was probably lucky because if I came in with the end budget to Lars back then he would have said, ‘No no no!’”

With the new site came an entirely new menu, “because we didn’t want this feeling of, ‘OK, this is just some new furniture and the dishes are the same’,” Munk says. He realised the attention his food was getting wasn’t always the right kind. “A lot of people also thought it was a restaurant that just wanted to provoke. It should not be ‘the restaurant with the live woodlice’, or whatever. It should be something more than that.”

As for the seemingly excessive 50 courses, he has a rationale. “When you have a set menu for five or six dishes and you have two meat dishes, you can’t serve woodlice or cow’s udder, because you will disappoint too many people. With 50 impressions, when we have maybe five meat dishes, we can allow ourselves to do things where some people will think, ‘This is disgusting, or not my style,’ and still think, ‘Well, there are still 40 other dishes that were great’.”

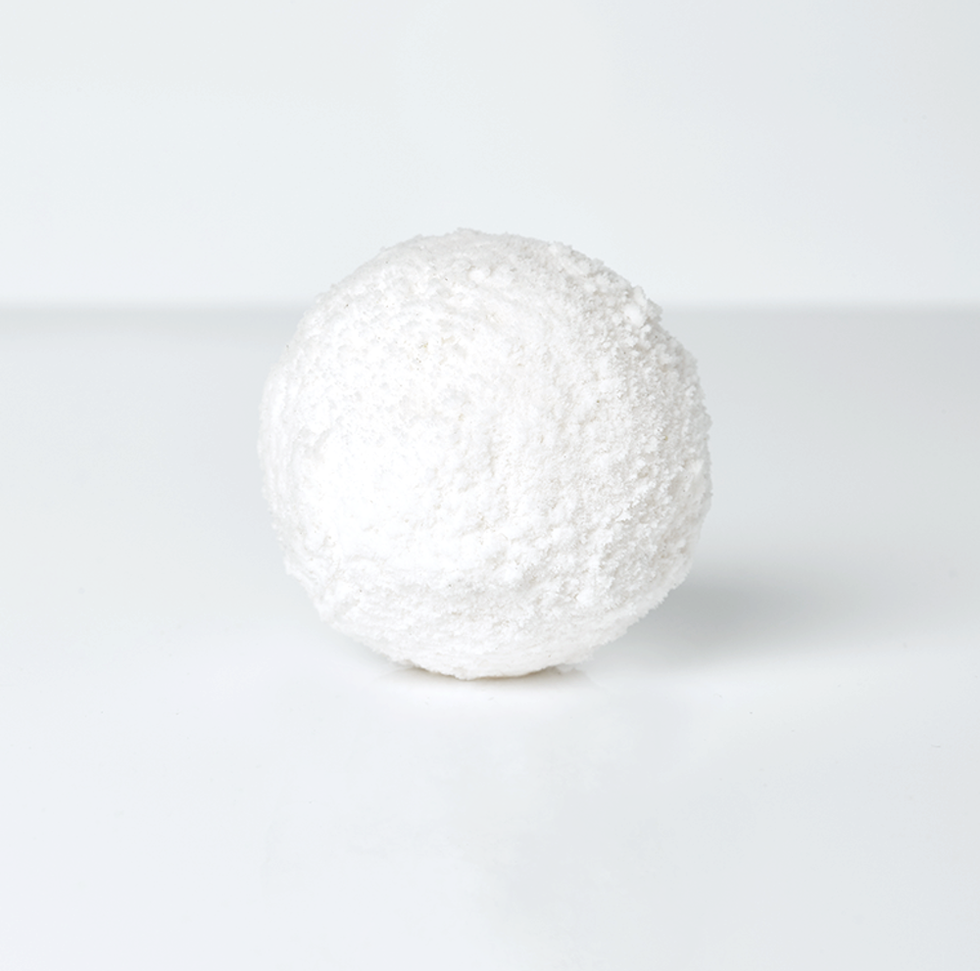

At dinner later that evening there was no cow’s udder, but there was a ball of puffed gluten that, when I bit into it, released a plume of wood smoke. There were ants preserved in “amber” that was actually a ginger and honey candy. There was a crisp, sweet, tomato-flavoured snowball which I was instructed to dip into olive oil while wearing special ski gloves (ski gloves!). There were lambs’ brains covered in cherry sauce and poached in walnut oil. There was a strawberry and rhubarb broth which I was invited to lick from a silicon human tongue (reader, I married him etc).

It was new and exciting and befuddling, and 90 per cent delicious (the unspeakable softness of the lambs’ brains, however, still haunts my dreams). Even though there are nods to his homeland — relax, sea buckthorn juice does feature on the menu — Alchemist feels like a move away from the Nordic ethos of simplicity and locality that has shaped food trends for the last decade or so. No diner at Noma just down the road is being proffered, as I was, a seahorse-shaped lollipop made out of sherbet flying saucers by a dancer in a corridor of zig-zagging neon lights intended, apparently, to raise awareness of LGBTQ+ issues. And very tasty it was, too.

Before dinner, I had asked Munk about relations between Alchemist and the other destination restaurants in Copenhagen. “I think there is friendly competition,” he said, before adding, “I also think a lot of them think this is stupid, because it’s so different from what they are doing. We go against what is the hot thing to do right now, and that’s a chance to take, but for me it makes sense. If I should do the other things it would not be me and my kind of cooking. I think it’s important that you need to stay true to yourself and your own thing.”

Alchemist, Refshalevej 173, Copenhagen, Denmark; restaurant-alchemist.dk

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox