Everyone is scared. A low-level thrum of anxiety has settled over the 2010s, along with a sense of rolling crisis. What’s wrong? Take your pick. There aren’t many parts of life right now that aren’t in some way troubling.

Which is perhaps why this was the decade in which horror cinema burst back into the mainstream. It’s always been there of course, lurking in the shadows. But in the 2010s, it was where a new class of filmmakers would make some of the most incendiary and politically pointed films of a turbulent decade, which attracted audiences and critical acclaim on an unprecedented scale. We’re all scared, but we all want to be scared, too.

“It's a genre that lends itself to saying things about existence and why we're here and what makes us all afraid and what makes us tick,” says writer and director Rose Glass, whose first film, the psychological horror Saint Maud, won a London Film Festival award in October. “But you can, in a way, hide some of those things behind the trappings of just an exciting, scary, entertaining film.”

Cinema reflects the time in which it's made, and horror has always been where society's deepest anxieties bubble to the surface. In the Seventies, as America addressed the fallout from the countercultural Sixties, demonic possession was big: The Exorcist, The Omen and Carrie showed that someone you knew could bring hell itself into your home. Toward the end of the decade and into the early Eighties, slashers like Halloween, Nightmare on Elm Street and Friday the 13th explored the vulnerabilities exposed by middle-class complacency and Reagonomics. Video nasties like Cannibal Holocaust showed that violence could invade anywhere. In the 2000s, when we were traumatised by terrorist attacks, revulsed by state-sanctioned torture, and bombarded with on-the-ground TV reports from Iraq and Afghanistan, horror was obsessed with gore, found footage and zombies.

But the 2010s saw something else take root. The last decade of horror isn't so much a genre. Unlike, say, the slasher flicks of the Eighties and Nineties, this new breed of films can't be grouped by shared story beats or masked villains. They're nothing like each other, which is what makes them part of a shared movement. Midsommar, Ari Aster’s woozy, splattery, very funny, Wicker Man-styled breakup drama which ends with (spoilers) a man being burned alive in a hollowed-out bear, is grouped in with the creeping dread of It Follows, which explores how a deadly, sexually transmitted curse ravages a community. Robert Eggers’ mud-spattered, Puritan-era slow burner, The Witch, sits next to John Krasinski’s dystopian sci-fi thriller A Quiet Place.

What really connects those films, and others – Jordan Peele’s witty, acerbic skewering of liberal hypocrisy Get Out, Aster’s child-decapitating coven drama Hereditary, the French cannibalism-as-teen-hazing shocker Raw – is their smartness. They’re brilliant, entertaining, thought-provoking films, which have not historically been the kind of adjectives associated with the genre. Hence why they've been lumped together under the handy, if controversial, banner of 'elevated horror'. “The cynic in me sort of worries that it sounds like a slightly snobby thing,” says Glass.

Call it what you want – elevated horror, arthouse horror, festival horror – there’s been a blossoming of original chillers in the last 10 years, and horror cinema is arguably where the most exciting new writer-directors have announced themselves. Jordan Peele, Jennifer Kent, Ari Aster, Robert Eggers and more have made it their playground, and the number of breakout horror hits cutting through to mainstream audiences, as well as getting critical plaudits, has been remarkable for a genre long associated with schlock, shock and a lack of artistic credibility.

So why have these auteurs emerged? The obvious answer is that horror is the medium that best expresses what it’s been like to live through the last 10 years, at least for anyone despairing of climate change, right-wing populism, social media screaming matches, or constant sense of being silently watched by governments and big tech companies.

Much like evil spirits, vampires and ghosts, these malevolent forces only start ruining your life if they’re willingly invited in. When everything starts to go wrong for the characters, the sting is in the fact that, on some level, it’s self-inflicted. Part of the thrill is in identifying with that masochistic impulse. Plus, the slower pace and emphasis on undefined anxiety and dread, rather than jump-scares and home-invading Big Bads, fits the prevailing mood. Where 9/11 was a single point of cataclysm, contemporary anxieties like climate change and political upheaval are a long, inexorable slide into chaos. By the time you realise anything’s wrong, it’s too late. The curse is on you.

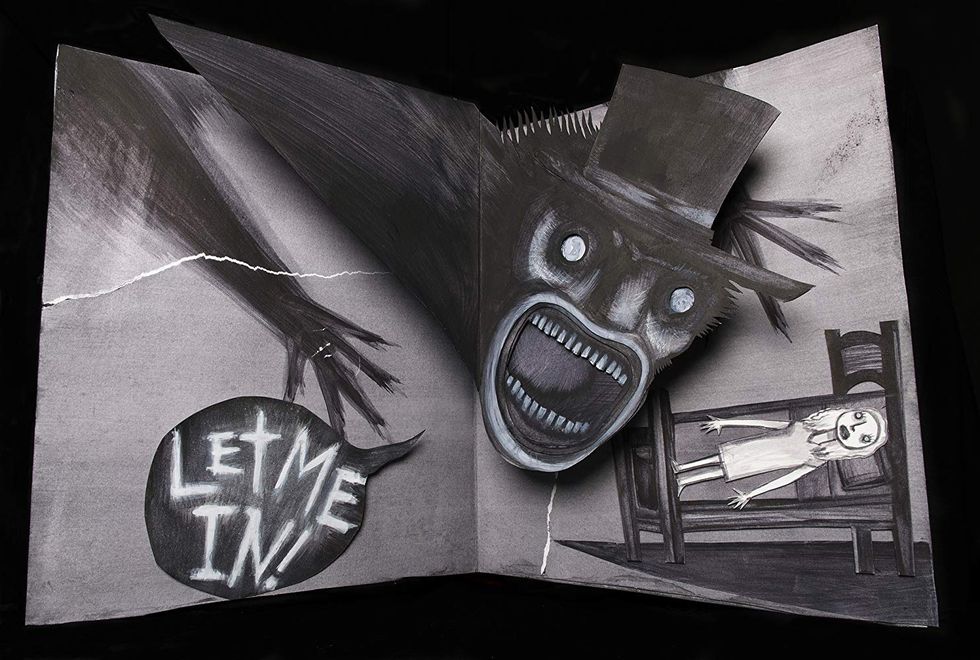

‘Elevated horror’ can be traced to two very different films, released just before the turn of the decade: 2007's no-budget poltergeist thriller Paranormal Activity, and Tomas Alfredson’s 2008 Swedish vampire tale Let The Right One In.

It was Alfredson's film that caught the eye of The Witch and The Lighthouse director Robert Eggers and turned him toward horror. Though its box office return was modest, he says that it showed that filmmakers could approach the genre in creatively rewarding ways. At the and of the 2000s, horror-adjacent (and award-winning) features by big name directors Darren Aronofsky and Lars von Trier furthered the creative appeal of a slower, artier horror. “Black Swan made money and Antichrist didn't," says Eggers, "but Aronofsky and Lars von Trier certainly added clout and prestige to doing genre film differently.”

If those films piqued the interest of filmmakers, it was Paranormal Activity that excited studios. Shot in a week for $15,000, it made $193.4 million and re-energised the found footage genre, which has been driven into the ground by a slew of post-The Blair Witch Project copycats.

Not that horror was on life support; rather, it had grown too big, according to film critic Helen O’Hara. “And that meant that you were kind of limited in what horror could do a little bit, and you started getting a slight softening around the edges in terms of ratings for some existing franchises, and you started to get lots of reboots and sequels.”

The likes of Saw, Scream, Final Destination and The Grudge milked once-interesting ideas for diminishing returns. But, O’Hara says, horror has “always, mostly, been a low budget genre”. The success of indie studio Blumhouse Productions, which produced Paranormal Activity and quickly earned a rep for making enormous amounts of money from tiny budgets, with films like Insidious, Sinister and The Purge. It gave horror directors an outlet for “slightly crazy notions and slightly bigger ideas,” says O'Hara, which could still compete at the multiplex. “They basically found a way to make horror pay, big time.”

In the 2010s, there were a few notable exceptions to the Blumhouse approach – It and A Quiet Place both cost north of $30 million, and The Conjuring, The Purge, Annabelle and Insidious all spawned franchises – but most hits have been made on much more modest budgets. The promise of creative freedom as a pay-off for thriftiness isn’t new, but this was perhaps the first time that heavyweight arthouse directors chose to work that way in horror, rather than more conventional dramas.

That’s not to say that the new horror is just about swerving the usual quiet-quiet-bang jump scares – those “unashamed horror beats” are as much a part of the horror filmmaker’s toolkit as ever, says Glass. Nor did they swing away from the ‘torture porn’ of Saw and Hostel with a more demure approach to gore; Ari Aster, in particular, likes to cave his characters’ heads in. The Witch and Midsommar take their time in telling their stories, but Get Out and The Babadook don’t hang about. “Me and Ari can bore you,” says Eggers. “Everyone else keeps it snappy.” Rather, since genre is now fluid in so much of pop culture, nobody’s too bothered about the pick-and-mix approach taken by different directors.

And that in turn is possible partly because of how easy it is to watch pretty much anything, at pretty much any time, thanks to the advent of streaming. More cine-literate audiences are more likely to appreciate films that assume they can keep up, rather than spoon-feeding them. As the big studios' tentpole features have become safer, horror has offered a smart and challenging refuge.

“Maybe [the] audience is just getting a bit more savvy,” says Glass. “Sometimes you go to the cinema, you want to know what you're going to see and for it to feel quite familiar. But I think because we obviously watch so much more stuff now, I think people are much quicker to sort of spot when something feels too predictable or too clunky.”

No film embodies that better than Get Out. In early 2017 it became a thinkpiece-generating cultural phenomenon, which made $255 million and earned a Best Picture Oscar nomination. Its success said a lot about how horror had changed since 2010. Most obviously, it was written and directed by what you’d once have called an auteur. Its director's follow-up, Us, wasn’t just marketed as a new horror film – it was the new Jordan Peele film. By the time it arrived you knew a Jordan Peele film meant as many laughs as scares, incisive social and racial commentary and inventive visuals. Aster, Eggers, Kent and John Krasinski have the same cachet. “There is a definite sense of personality there, and there's a definite sense of a single guiding hand there, a single set of obsessions,” says O’Hara.

That matters because the idea of an auteur plants these horror films in traditions that are “already culturally endorsed”, like literary novels, says Cecilia Sayad, head of the film department at the University of Kent. The implication is that these films are not prey to the meddling and adulteration that other films are, even if that’s not strictly true.

“They might [have] this kind of untraceable origin, but we like to think about works of art as somebody talking to us or somebody telling us a story,” Sayad says. “I think it's very appealing to think that there is like a human mind behind this, no matter how many other professionals might help or contribute to that.”

Freed from the expectations that come with big budgets, these writer-directors are free to address “more granular and slightly more specific fears,” says O’Hara. Get Out's power comes from the truth and clarity of its satire, not just of racial injustice in America, but of a particular strain of complacent racism among white, middle-class America that leads to the colonisation of black bodies. Similarly, Jennifer Kent's The Babadook – in which a recent widow battles a monster that haunts her son – articulates grief and maternal rage in unique and raw way.

Horror has also been quicker than other genres to open its doors to creators who aren’t straight white men. “This is where diversity is more than a catchphrase and this is why diversity has a value beyond being morally the right thing to do – it gives us better movies,” O’Hara says. “If you are a film fan, you should care about diversity because it will give you better movies, it will give you more interesting viewpoints, it will give you stuff that you haven't seen before. And that's something that we should all want.”

Beneath all of this, though, is the fact that horror cinema still does what it always has done. These films don’t tend to dwell on civil unrest – as O’Hara points out, “the idea of going to the cinema and watching social breakdown is not appealing at all right now. Apocalypses, same deal” – but they still help to fight the loneliness that can settle on you when you mostly keep up with what your mates are doing via Instagram Stories. You sit down in the dark with a group of other people, and you all gasp in unison. As Glass puts it: “Oh, you got it as well?! We feel the same way – great.”

At a time when the world can feel divided into scrapping factions – especially when you’re used to experiencing things at a remove via social media – involuntarily screaming discharges that anxiety safely, and in a way that makes you feel more connected to other people.

This decade was scary, so perhaps this new breed of horror films were about scaring us in ways we could control. We wanted to purge that lingering sense of unease and tension and chaos through something we thought we understood the boundaries of, and which, once the adrenalin had subsided, we could feel quite clever about afterwards.

Then again, it might be even simpler than that. “Maybe,” says Glass, “we're all just very afraid at the moment.”