Following the news that Al Pacino will be joining the cast of the upcoming Amedeo Modigliani biopic, directed by Johnny Depp, we're revisiting our 2019 piece on the Italian-American actor's thwarted attempts to get the film made in the 1980s.

When The Irishman was first announced in 2014, most headlines focused on the prospect of a reunion between Martin Scorsese’s greatest gangsters: Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci and Al Pacino. Of course, no finger-wagging film buff worth their IMDb Pro account could pass up that kind of open goal.

“Well, actually,” they all piped up in unison, eye-rolling the Earth off its axis. “That's a common misconception. Martin Scorsese and Al Pacino have never worked together. Actually.”

And it was true. Pacino had starred alongside De Niro multiple times, in Heat and buddy cop movie Righteous Kill, as well as in The Godfather: Part II. But he'd never performed with Pesci before his Netflix debut and somehow, through some kind of tear in the fabric of time, had never collaborated with Scorsese either.

But that doesn’t mean the shared desire wasn’t there, or that they didn’t come close. Back in the Eighties, the pair teamed up to pitch a biopic about the tragic 20th century painter Amedeo Modigliani, but were foiled by their own faltering box office returns and a Hollywood system in panic mode.

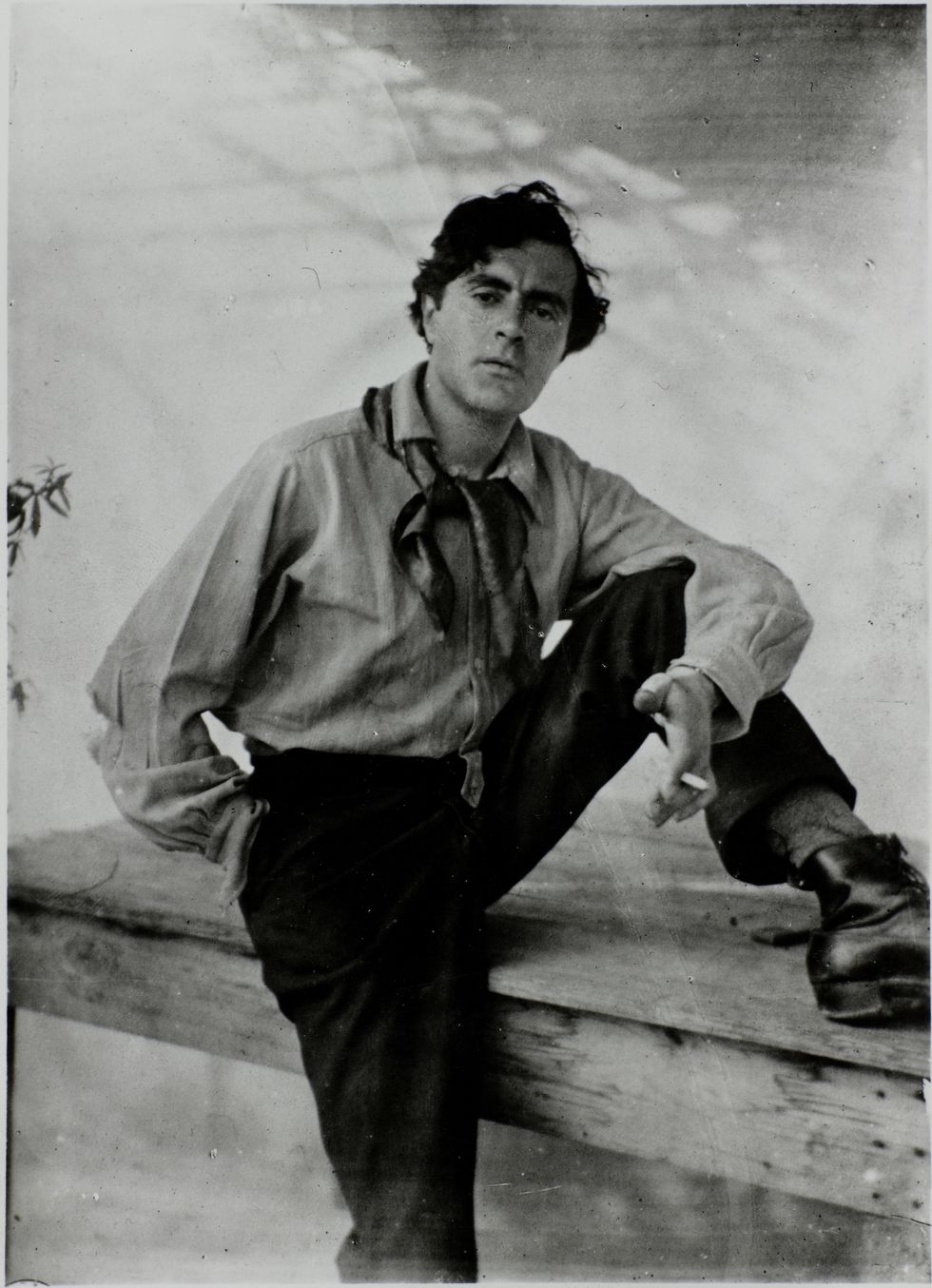

It was Pacino who first wanted to bring Modigliani’s scandalous life story to the big screen. The Italian-Jewish artist, best known for his controversial paintings of nude, long-limbed women, was regarded as an inveterate playboy and drug addict in the early 1900s and died from tuberculosis at the age of 35 (closely followed by his pregnant wife, Jeanne Hébuterne, who threw herself out a window two days later). His opium-fuelled exploits in the bohemian backstreets of Paris were made the subject of an off-Broadway production, ‘Modigliani: A Play In Three Acts’, by Dennis McIntyre in the late Seventies. Pacino was certain it would make a great film.

He convinced Keith Barish, an entrepreneur-turned-free spending film financier (who went on to co-found Planet Hollywood) to buy the rights for £100,000 in the late Seventies and give Pacino complete creative control. Once the deal was done, Pacino flew his friend, Richard Price, to Paris to write a screen-play. “Pacino has always wanted to play Modigliani, and this purchase gives him an opportunity to work with a writer and bring in a director he likes,” Barish told the New York Times in 1979. “We won't be filming the play, which covers three days in Modigliani's life when he was starving in Paris and trading his paintings for bread. The play will simply be the basis for a movie script.”

At the beginning, Scorsese was only Pacino’s second or third choice to direct the movie. “I’ve given it to Coppola,” he told Lawrence Grobel in the December 1979 issue of Playboy. “If he doesn’t like it, I’ll give it to Bertolucci or Scorsese.”

Al Pacino’s preference for Francis Ford Coppola was understandable. The pair grew close after the director fought with studio heads to cast the actor as Michael Corleone in The Godfather, and he was coming off the back of a Palme d’Or win for Apocalypse Now (which Al Pacino turned down for fear of falling ill in the Dominican jungle). Coppola was the undisputed heavyweight of Hollywood movie-making. Scorsese, on the other hand, was on the ropes.

Following the surprise financial success of Mean Streets and Taxi Driver, Scorsese was entrusted with a bigger budget for his 1976 musical New York, New York, starring De Niro and Liza Minelli. But the film earned just a little over its $14 million budget, and ruthless critics suggested the 32-year-old auteur simply couldn’t handle the pressure of a huge Hollywood production. Scorsese took the backlash personally, accusing them of treating his box office failure as some kind of “comeuppance” for his arthouse success.

But problems mounted long before the bad reviews. According to Peter Biskind’s book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, Scorsese struggled heavily with drug addiction throughout filming, which he spent “fuelled by a perpetual coke high”. It meant that he failed to meet his own standards, ultimately losing control of the set and his vision. “I was just too drugged out to solve the structure,” he later admitted.

He wasn't alone. This was an age in which cocaine was so widespread and readily available that many Hollywood figures wore small gold spoons on their necklaces. But the depression that formed from New York, New York’s failure proved hard to overcome, and a course of lithium failed to salve his bouts of anger. His close friend, Robert De Niro, tried to help, suggesting that he pour himself into a project based on the autobiography of underdog boxer Jake LaMotta.

“I really didn’t want to do Raging Bull," Scorsese later told Biskind. “I had to find the key for myself. And I wasn’t interested in finding the key, because I’d tried something, New York, New York, and it was a failure.”

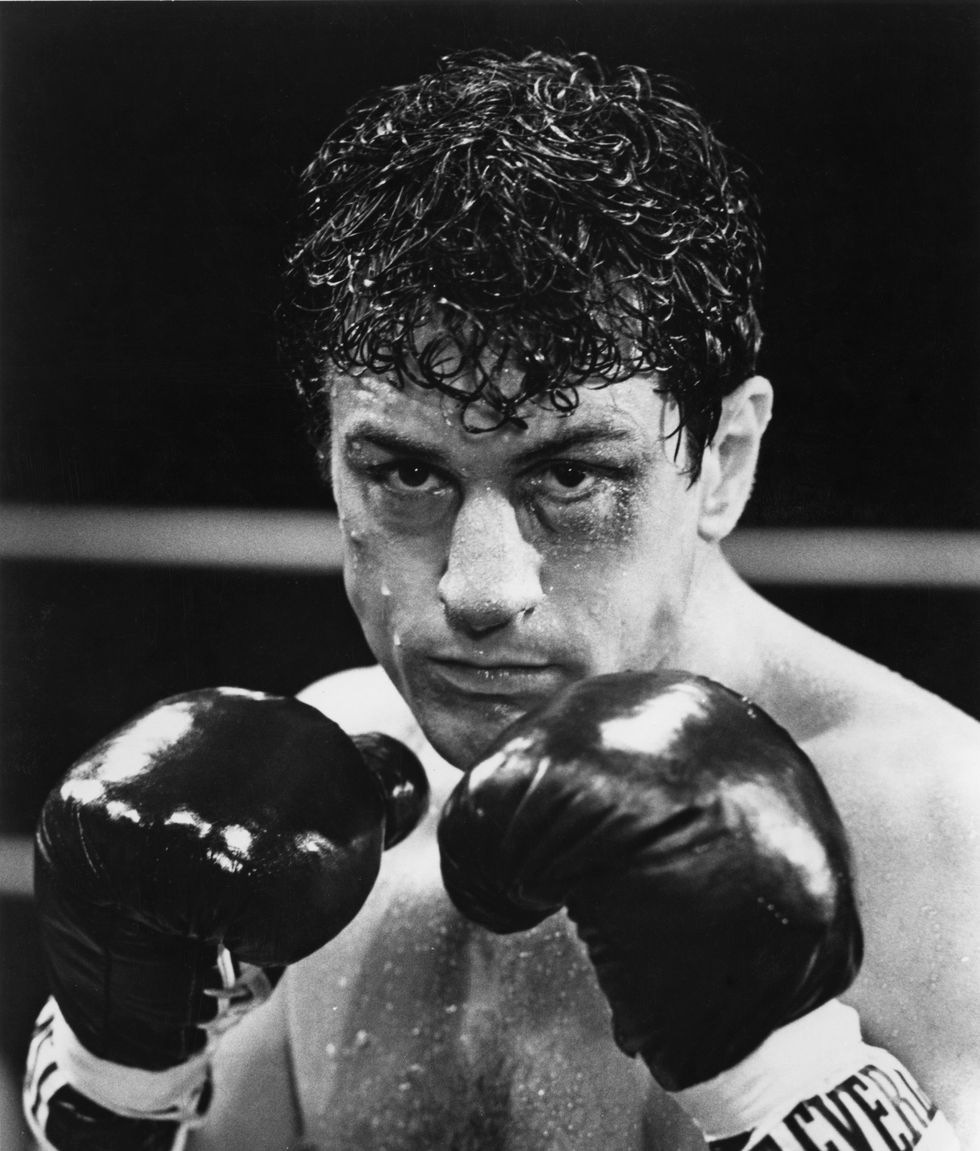

Eventually De Niro succeeded on both fronts. After Scorsese suffered a drug-induced hospitalisation and near-death experience, the actor helped hi kick his cocaine habit for good and finally convinced him to direct Raging Bull (despite his lack of interest in boxing and sports in general). The 1980 film, shot in black-and-white and featuring Joe Pesci in his first major role, went on to win two Academy Awards. It’s often credited as being one of the greatest films of all-time.

Although, not at the time. It opened to mixed reviews and made just $5 million over its budget. While it fared better than New York, New York, Scorsese’s underwhelming box office returns were hurting his ability to demand big budgets from studios. Then came Heaven’s Gate.

In 1978, Michael Cimino won the Best Director and Best Picture Oscars in 1978 for The Deer Hunter. With studios begging to work with him, he parlayed that success into complete creative control for his next feature, a star-studded western that he wrote and directed. But when it arrived in November 1980, Heaven's Gate recouped just $3.5 million of its $44 million budget. The impact on the Hollywood system was huge, signalling the end of an era in which young, talented directors were entrusted with sprawling budgets and boundless creative freedom.

“What happened is that the whole industry changed,” Scorsese told Associated Press this year. “We opened Raging Bull nine or ten days before the same studio, UA, released Heaven’s Gate. And then Heaven’s Gate was closed by one review from The New York Times and that was the end of what’s derogatorily, unfortunately, referred to as the ‘auteur’ cinema of America. It was destroyed.”

The lukewarm reaction to Martin Scorsese’s mid-Eighties follow-ups, The King of Comedy and the low-budget After Hours, continued to hurt his studio clout. And yet Pacino still turned to Marty after Coppola turned down his Modigliani project. He had almost worked with Scorsese on 1973’s Serpico, and now it finally looked like it might happen.

Scorsese loved the screenplay, telling Empire magazine this year: “It was about the extraordinary struggle to create art. The sadness of it, the absinthe […] He and [his companion] Soutine taking care of each other, with her convincing him to brush his teeth. It really would have been something special, I think.”

Despite the pair’s shared star power, it was far from a foregone conclusion. Scorsese’s passion project, The Last Temptation of Christ, had been shelved three years earlier due to budget constraints, and the surprise success of Star Wars and Jaws had set Hollywood on a different course.

They shopped it around studios, but faced constant rejection. “Someone who was a big producer in Hollywood said to my face, ‘You’re washed up. Where are you going to get the money to do it?”, Scorsese recalled in his Empire interview. “I didn’t have the influence anymore. I was from a certain period — the world had changed and you just weren’t bankable, as they say.”

“At that time I really couldn’t get anything made. Nothing,” he told Sight & Sound this year. His luck would soon change with the box office hit The Colour of Money, but by that time the project had passed him by. “I couldn’t get the financing in the 1980s. Then he went with [directors Brian] De Palma and [Sidney] Lumet, so it’s a whole other thing,” he told Spike Lee’s Director’s Cut podcast.

Meanwhile, Al Pacino’s passion for the project appeared to wane. His role in 1995’s Revolution was a commercial and critical failure, which may have had some influence on his unexpected decision to take a four year hiatus from film and return to theatre.

The early nineties were a more successful time for both Scorsese and Pacino. Goodfellas, Scent of a Woman and Carlito’s Way all raked in money and acclaim. But Armedeo Modigliani never drifted from their thoughts entirely, and when a script from a young Scottish writer called Mick Davis arrived on Scorsese’s desk, the wheels started to turn again.

“Martin Scorsese told me it's one of the best screenplays he's ever read and could turn into either a movie or a theatre performance,” Davis told Romanian publication Ziarul Metropolis in 2014. The director advised that he be signed up to a big Hollywood agency. "Scorsese never made the movie,” Davis told The Independent in 2014. “But it got me in the door."

The script found its way to Al Pacino and 20th Century Fox (who owned the rights to the film by that point). Seeing potential, they suggested Davis combine his script with the previous version shopped around by Scorsese. Al Pacino, now too old to play the main role, considered directing, and Johnny Depp was even touted for Modigliani. But Davis says he struggled to make it work.

"I hated the script because the play took the spirit out of the character and made him dark and depressed. I wanted to do a movie about a man who loves life. I got scared because that beautiful story was going to be taken by somebody else," he told The Independent.

When the studio’s option ran out, Davis took the brave decision not to renew and pursued the project himself. "Everybody thought I was mad, but I wanted to do Modigliani my way." He spent a decade fighting to get the £10 million art-house film funded and finished, ultimately directing the movie himself, all in a bid to prove the doubters wrong.

But sometimes the doubters are right. Released in 2004, Modigliani was a critical and commercial bomb, currently sitting at four per cent on Rotten Tomatoes. Starring Al Pacino's much-too-old Godfather III cast-mate Andy Garcia as the tragic painter (he was 48 at time of filming), The New York Times described it as a "textbook outline of how not to film the life of a legendary artist."

While Davis's filmmaking chops can be called into question, his dedication to Modigliani's memory surely can't. "I spent years really struggling to climb this mountain. The project died so many times, but I never gave up," he said at the time of release. "It is the story I wanted to tell."

In the forty-odd years since Hollywood turned away from auteur-driven cinema, spendthrift streaming services have arrived to fulfil that same role. Which begs the question: if a Modigliani nude can still fetch $157 million at auction, how much would Netflix pay to reunite Scorsese and Pacino for one last passion project? This time around, you imagine they'd have stiff competition.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more delivered straight to your inbox