Earlier this year, a friend’s eleven-year-old daughter came to lunch with us. She was wearing a black t-shirt, with 'Friends' emblazoned across the chest, in the hole-punched font that no one of a certain age can see without thinking of smelly cat, pivoting, and "We were on a break!". She asked me if I’d seen the show, in the same voice I might use to explain the ‘feral hogs’ meme to an elderly relative.

Edie was born four years after Friends ended. She uses her phone to film riffs on TikTok trends, listen to Billie Eilish, and watch the travails of Ross and Rachel, a couple who feel just as much a part of her generation. The show transports her to a simpler, more golden era, even if it’s one she didn’t personally experience.

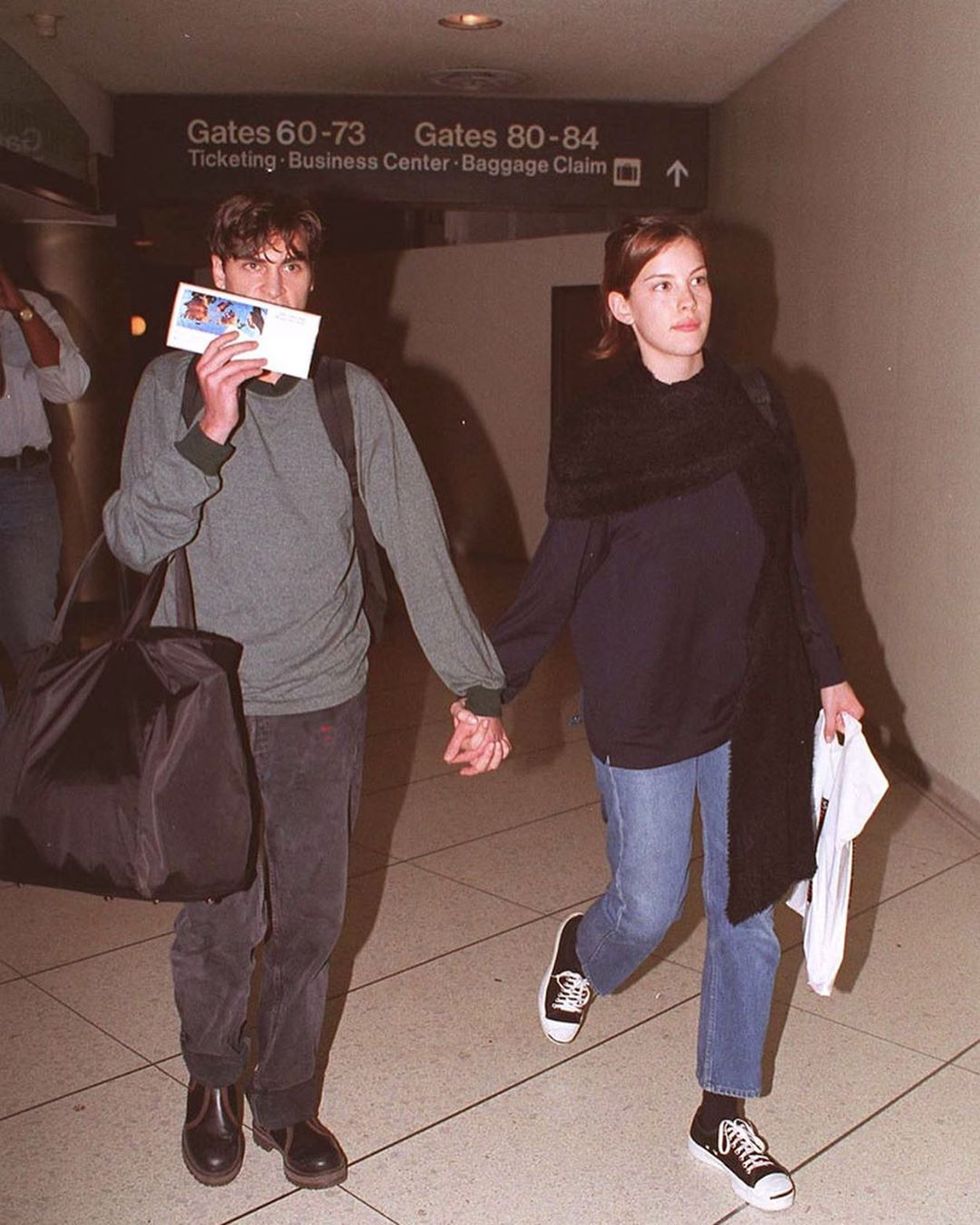

This sense of being nostalgic for something you have no memory of is how I feel when I look at the Instagram account @90sanxiety, a profile with nearly a million followers which documents the decade I grew up in, but was too young to truly experience. There are photos of Joaquin Phoenix and Liv Tyler at LAX, or Jennifer Aniston with corkscrew curls sat on a rope swing. Appearing between Instagram’s ubiquitous doe eyes and pillow lips, they’re arresting, like portholes into a time that appears, to me at least, simpler and more golden.

It feels as though we’re living in an era in which nostalgia is more pervasive than ever: there in emotion-manipulating supermarket ads or the fancy dress themes to friends’ birthdays. Online, the past is bait to distract you from the now, with social media springing warm and fuzzy memories on you, to avert your eyes from depressing news cycles. The cinema is bloated with remakes of Disney classics and the small screen with reboots of old shows, as pop culture digs up its past and sells it as new. It can feel as if the present has become too much to bear, and so we're trying to retreat into a version of the world we're more comfortable with.

People often ask Tim Wildschut if we are more nostalgic now than we have ever been. A professor of social and personality psychology at the University of Southampton, Wildschut is the co-author of several landmark studies examining its triggers and effects. Working with his colleague, Constantine Sedikides, he's helped change the perception of nostalgia from a symptom of conditions like depression to a universal emotional effect, experienced seemingly in all cultures and all societies, that acts like a kind of cognitive shield during times of emotional stress.

In the late-Nineties, Sedikides had moved to Southampton from Chapel Hill, North Carolina, where he soon began to experience strong, nostalgic feelings for his former home. Memories of basketball games, or the smell of an autumn evening, would flood back to him unbidden a few times a week. He mentioned them to one colleague, a clinical psychiatrist, who diagnosed him with depression – he was clearly living in the past because he was unhappy with his present. But that didn't feel right to Sedikides. These weren't sad memories. He didn't want to go back to Chapel Hill, but remembering his life there made him feel happier about the communities he'd built, and was building in his new home.

He discussed his feelings with Wildschut, a fellow émigré, from Utrecht in the Netherlands. The pair realised that Sedikides's view of his own nostalgia ran counter to the way that science had thought of it for more than 300 years. Curiosity piqued, the pair decided to investigate. "Among academics, there’s a saying that ‘research is ‘me-search’," says Wildschut. "So in a sense it was our own personal experiences which inspired it, but we realised it was a very neglected topic.”

'Nostalgia' as a term was coined in 1688, by Swiss military physician Johannes Hofer, to describe the debilitating homesickness that mercenaries suffered while fighting in foreign countries. Combining the Greek words ‘nostos’ (homecoming) and ‘algia’ (pain or suffering), it was considered similar to seasickness: that living at a distance from the place you were born could cause lethargy, fever and stomach pain, just as waves rocking a ship might spark nausea.

Though it was still being diagnosed in soldiers until the 1870s – supposedly 74 Union men died of nostalgia during the American Civil War – by the 20th century it had come to be seen as part of a wider suite of maladies. Depressives, for example, might dwell on their past, obsessing over choices and decisions they had made and how their lives might have been different. It wasn't until the late-20th century that researchers split nostalgia out as a separate emotion from this kind of rumination. They came to see nostalgia as a feeling, rather than an action.

Nostalgic memories are intimately bound up with emotions, and by accessing the former, we trigger the latter. That's why studies have shown our fondness for the music we listened to as teenagers – and gradual, Grandpa Simpson-like rejection of new pop as we age – is as much a function of our neurology as our capacities as music critics. When we're younger, we feel emotions more strongly, especially those linked to cues from music (only love and drugs top it for inducing a cascade of the pleasure chemicals dopamine, serotonin and oxytocin). Young brains are more plastic, and that cocktail of neurotransmitters, coupled with music's increased importance as a social bond when we're young, embeds it with strong emotional memories; the song that played when you had your first kiss, say, is imprinted in your brain like a handprint in wet concrete. When you hear it again 30 years later, that memory is activated. Nostalgia rushes through you. Similarly, smell and taste – think of Proust's madeleines – can have the same effect.

This is where nostalgia differs from recollection. Brain scans of people experiencing nostalgic feelings show activity in the amygdala and hippocampus, primitive parts of our brain that form part of the autonomic nervous system, which regulates our body's unconscious activities: pulse, digestion, sexual arousal. Research shows that nostalgia is similarly involuntary, even if, like arousal, it can be deliberately invoked.

Wildschut sees nostalgia as a form of emotional homeostasis, part of the body's attempts to return itself to a point of equilibrium. If we're unhappy, stressed or depressed, research shows that we're also more susceptible to nostalgic feelings. “When people experience disruption in their lives, maybe a divorce or bereavement, that increases their level of nostalgia. Something happens that’s negative and it triggers nostalgia which stabilises you and brings you back to a more positive state.”

To study nostalgia's effects, and the kind of people who are most susceptible, Wildschut and Sedikides created a questionnaire, called the Southampton Nostalgia Scale, to identify the traits of nostalgia-prone people. Studies based on the scale have shown it can physically warm the body on cold days, make us more tolerant of outsiders and help to counteract loneliness and anxiety. Nostalgia also increases our resilience and positivity about the future, making it a uniquely powerful emotion to harness during the increasingly turbulent times we are living through.

As an emotion, nostalgia is bittersweet; we recall happy moments, but they are distant. That means it also unreliable. Nostalgic memories are invariably positive, stripped of any counterbalancing negative experiences. We remember falling in love for the first time on holiday, but forget the heartbreak when we returned home. We remember the feel of sun on our skin, but forget the burns we suffered through the next day. Nostalgia is the perfect past, but it never really existed. Yet we return to it, like a drug, when we need it to make us feel better.

Wildschut believes that we are no more or less nostalgic than we were in the past, it's just that the tools around us make it easier to indulge. "In the past, people would have photo albums or diaries or art,” he says. “The internet means nostalgia is at your fingertips."

Nostalgia’s power to emotionally stabilise you is part of why we reach out to it for comfort when disorientated. On evenings when I arrive home having watched four full trains go past me, and having dropped my keys trying to get into my flat in the dark, putting on an episode of Seinfeld feels like bubblewrap for my brain.

For many people I know, it’s Friends that steers them back on course. The jokes ping-pong between the same six familiar voices, the wallpaper never changes, and the laughter track of the audience jingles every minute or so. When I told a friend I was writing this piece, she admitted she puts it on every night to fall asleep.

On a grey Friday afternoon in December, The Truman Brewery on Brick Lane, East London is filled with people wandering around set recreations of a living room, coffee bar, even a narrow hallway, which are instantly recognisable to most people who have watched television over the last 25 years. Comedy Central’s FestiveFriends is a Christmas spin on the live event, which has run for five years, with recreations of the sitcom’s sets offering fans the chance to pose next to the giant rubber turkey wearing sunglasses.

The entrance way plays the show’s theme song on a loop, joyfully telling those untangling scarves and coats, “I’ll be there for you”. There are couples posing with Monica’s fat dress and mothers shepherding groups of teenage girls into Chandler’s apartment. The labyrinth of rooms has the engineered festivity of a candy cane cappuccino. A group steps in front of a photo opportunity, hands their phones to the strangers behind them, poses, reviews the images, then moves on. Then the strangers step up and pass their phones back. Groups are moved from set to set on tight time schedules, so everyone gets a photo in every spot. Every ten minutes or so, visitors are instructed to clear the set so that everyone can get a clean shot of the apartment.

Lou, who has “kept all the videos and still watches them,” is here with her friend, Debbie. For them, Friends has endured since childhood, there for them even as they grew up, got married and had children. They are, one would think, FriendsFestive’s precise target market. But all around them are people born too late to have seen the show first time around. Maisie, a 14-year-old attending with her mum, tells me all her friends love the show for its warmth. “It’s the friendships that make it feel nice.”

Sophia and Hardev have come down to celebrate a friend’s 21st birthday. They both spend their time at university rewatching episodes, which they estimate they’ve seen hundreds of times. “It’s something to take your mind off things, so I have it on every night,” Sophia says. “It’s not got much filter, whereas now we have to be really careful what we say. With Friends it’s so light-hearted.”

I know Friends, but I’m not a Phoebe or a Monica. I’ve never sat down with the intention of watching it, and yet over the years I’ve probably seen all 236 episodes. Ninety hours of TV consumed almost unconsciously. There’s a lack of reality to it that is comforting to sink into. Its 10 seasons, starting in 1994 and wrapping a decade later, somehow encapsulate New York in that era and yet feel entirely disconnected from it. The clothes, the coffee, yes. The rising inequality, the 9/11 attacks, not so much. In Friends, reality is inconveniently heavy, so it’s ignored. For viewers today, that makes it a welcome relief.

When Friends celebrated its 25th anniversary in 2019, many commented on how poorly the show had aged. Watched from our more woke vantage point, the gang’s gay panic, its transphobia, its fat-shaming and relegation of people of colour to plot points, are jarring. And yet it’s never felt more popular. In 2019, it was Netflix’s most streamed show in the UK for a second year running. Robert DeNiro’s company even announced it was suing an ex-employee after they watched 55 episodes of the series over four days at work. The internet responded with relief that they weren’t the only ones spending their evenings with Monica and Chandler.

Friends came to a close just as The Sopranos and The Wire kicked off TV’s so-called ‘golden age’. The best TV of the last two decades has been intense, thought-provoking, and subsequently, more difficult to watch. Perhaps that explains our retreat into nostalgia, abetted by studios rebooting shows like Gilmore Girls and Will & Grace. We spend our days in front of screens which broadcast us more information than we’re able to handle about things we aren’t able to change. Is it any surprise that safe and familiar relics are being dug up to soothe us?

On the big screen, 2019 alone featured reboots and remakes of The Lion King, Jumanji, Cats, Aladdin, Men In Black, Charlie’s Angels and Dumbo. This fixation with the past is arguably a direct result of our economic uncertainty, political upheaval, and rapid advances in technology – unsettling times have caused us to turn away from the future and crawl back under the duvet of the familiar.

There's also the fact that studio executives know that there’s money in repackaging something we already know intimately. As Martin Kaplan, director of the Norman Lear Center at the University of Southern California, told the New York Times in 2016: “There’s nothing as helpful to a programmer as a title or a show that has brand equity already built into it.”

Every reboot or remake is markedly poorer art than the original that inspired it, and yet 2019’s top-grossing films – Joker aside – are all either sequels or reboots. It’s as though everyone is too exhausted to have to learn a new set of characters and plots. Instead, they walk into cinemas to revisit old friends in a brightly glowing past. Audiences get characters they can remember the names of, in a plot they’ve already chewed through, like easily digested, entertainment stodge.

In his 2011 book Retromania, music writer Simon Reynolds dug into what he called “pop culture’s addiction to its own past”. The idea for the book came out of discussions he was having on blogging forums. “We would have debates about the backward-looking nature of so much music in the 2000s,” he tells me. “How there hadn’t really been a wave of innovative music, at least on the same level as rave culture in the Nineties, or hip-hop in the Eighties.”

Discogs, an enormous forum where music fans can rate, share and sell their records, launched in 2000 and quickly became a place to geek out on rare releases. When YouTube launched six years later, the same obsessives began uploading their music there, too. Streaming services made out-of-print music catalogues accessible and gave you almost every song ever made available as soon as you remembered it.

Legacy bands like Pixies were beating out new acts to headline festivals and the charts were filled with artists inspired by the sounds of bygone eras, from Amy Winehouse to Adele to Gnarls Barkley. “Peak retro for me was that album Daft Punk did that’s not appearing on any of the ‘best of 2010s’ lists [2013’s Random Access Memories],” Reynolds says. “It was a massive gesture of breaking with digital technology, using studio musicians and a real drummer and [going] back to the late-Seventies golden age of funk and disco.” It was just as nostalgic lyrically, calling on the likes of Pharrell, Giorgio Moroder and Julian Casablancas for songs about memory and the space race.

“I was depressed and alarmed by it,” Reynolds says. “I wondered, ‘Is this going to go on forever?’ The idea of ‘pop culture’s addiction’ was sort of like a drug, but also a resource like oil running out. How many times can you go back to the Sixties and recycle them?”

Eight years later he feels less dismayed, seeing in auto-tune, at least, some signs of genuine musical innovation. “What everyone thought of as a gimmick when Cher did it with 'Believe' actually became an artistic tool, and there were all kinds of people using it: Kanye West, Future, Migos,” he says.

Reynolds doesn’t believe we’re more nostalgic now than ever; as he points out, the Seventies bands who Daft Punk venerated were just as reverential of those from the Twenties and Fifties. What’s changed is that they were choosing to actively explore that history; today, we’re bombarded with tools that lure us into revisiting the past.

On the day Reynolds moved from New York to Los Angeles with his family, they took a photograph on his phone of their shadows stretched out over a pavement. Years later, Facebook served him up the photograph as a suggested memory to share. He was used to his ‘suggested memories’ being the meaningless flotsam of life. That the algorithm had landed on something genuinely meaningful unnerved him.

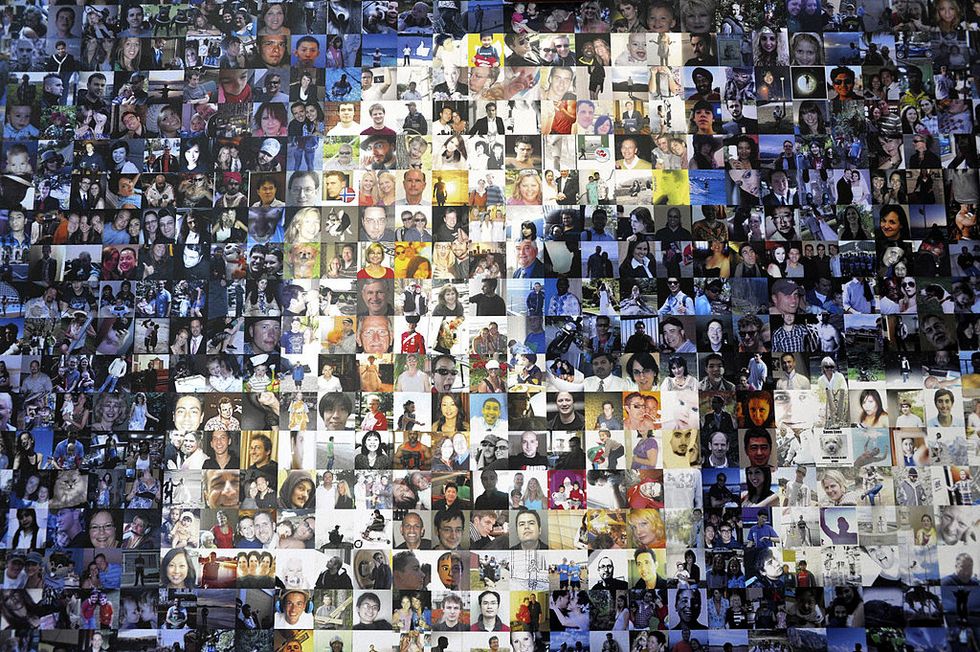

Every corner of social media seems to be using nostalgia to emotionally manipulate us, beaming us something warm and fuzzy on a cold, shiny screen. When Instagram launched in 2010, the app’s initial appeal was offering retro-looking filters for modern photographs. In November 2019, it added an ‘On This Day’ feature to Stories, the same nostalgia-inducer that already exists on Facebook and is the basis for the app TimeHop. Apple's iPhoto has long proffered up memories manufactured from the tens of thousands of photos we now take every year.

Today, I can take a trip through events as meaningful as ‘St Andrews days over the years’. Though I know they are nothing more than memories engineered by an algorithm based on date stamps and common pixels, I still catch myself sending them to friends, adding, “Five years ago!” as though the time that has elapsed means anything.

I created a Facebook account when I was 14 and, like all my friends at school, used the album function as a limitless deposit for my embarrassing, unedited life. The photoshoot my friends staged on a South West train and a pre-funeral selfie were uploaded without a thought to whether I might want these moments to live forever. These carefree days were an extension of first-generation social media platforms like Flickr or Tumblr, which offered endless storage to create virtual photo albums.

In the last three years, it’s become increasingly apparent how personal data – even our memories – can be weaponised. At best, it might mean I see more ads for things my teenage self would have wanted. At worst, that Russian content farms can target me with political ads. The trust we place in platforms like Facebook to act like a warehouse for the detritus of our lives has boiled away as data scandals, fake news and a flow of unchallenged hate speech has made being online in 2019 feel like a car alarm is going off in your skull.

Yet many of us are still reticent to leave the places that we see as the gatekeepers of our memories, even as the data which Facebook has sold out from under us is the very thing that we are being manipulated into staying around for. When I decided to delete my Facebook account two years ago, I hesitated, as though I was destroying my actual memories.

“One of the biggest selling points of these platforms that have had you on there for such a long time is the nostalgia porn,” says Tama Leaver, associate professor in internet studies at Curtin University in Australia, and author of recent book Instagram: Visual Social Media Cultures. “They know your memories are incredibly valuable to you.

“Facebook struggles to keep the personal and feel-good stories up top,” he says. “Most people don't log into Facebook to hear more about climate change and mass shootings, but that tends to be what we get. The current internet feels just as grubby and dirty as the world around us, either covered in snow or fire, but not much in between.”

In a feed punctuated with despair, faces of your friends and memories from your past are little lighthouses beaming through the storm. Our memories, and their power to trigger positivity, are what keep us walking through the fire or tramping through the snow, until we stumble across a hit of something that feels good.

The internet’s rubbish heap of bad news is disorientating. Dusting it with nostalgic memories hits us when we’re most vulnerable and makes it easier to gobble up what’s underneath. We’re not more nostalgic now, we’re just more exposed to things that make us nostalgic.

Today’s internet is a crueler, more spiteful place than when most of us first logged in, first tweeted, first uploaded a selfie. As New Yorker writer Jia Tolentino wrote of the internet in her essay collection, Trick Mirror, “at one point this all felt like butterflies and puddles and blossoms, and we sit patiently in our festering inferno, waiting for the internet to turn around and get good again, but it won’t.”

This waiting around is scrambled by the way that the internet bends our sense of time. As Reynolds puts it in Retromania: “On the internet, the past and the present commingle in a way that makes time itself mushy and spongiform.” The algorithm keeps showing you a post from two days ago, while the last two years feel muddled. Just as nostalgia was first thought of as something like seasickness, our digital nostalgia is a symptom of these waves of the past and present, crashing over us again and again.

Few industries are as plagued with the sentiment that it ain’t what it used to be as journalism. The big four tech firms – Google, Facebook, Amazon and Apple – have swallowed advertising revenue, while much of online journalism has struggled to convince readers to pay for what they feel should be free.

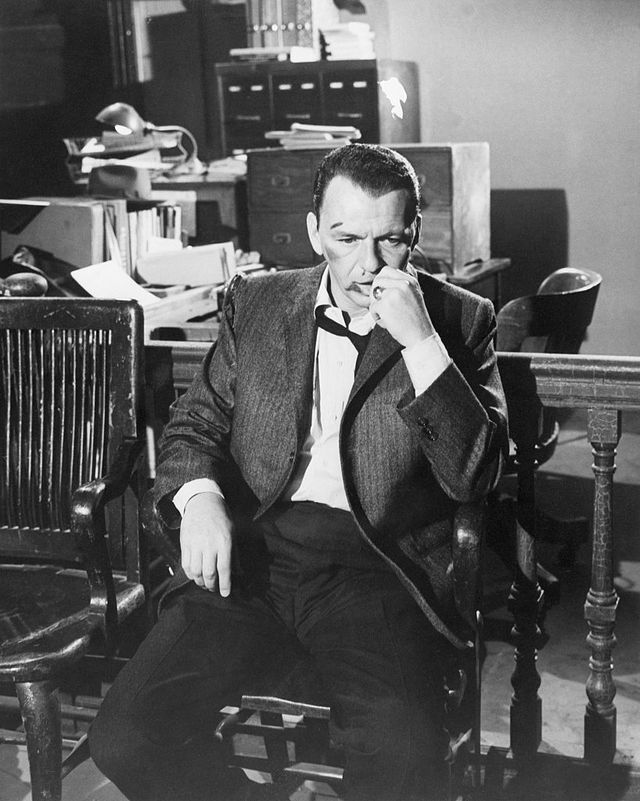

My entire career I’ve heard reverent whispers about the glory days, where you were put up in New York for a week-long sojourn with a celebrity and every lunch had a three martini minimum. While reporting the greatest profile ever written, ‘Frank Sinatra Has A Cold’, Gay Talese followed the singer around for three months and eventually filed a $5,000 expense claim (about $40,000 today). It certainly sounds more glamorous than meme round-ups.

But nostalgia smooths out the baggage of the time. These stories were likely to be about, and written by, straight, white, affluent men. Diversity in journalism then was even worse than it is now – as a woman working at Esquire in the Sixties, I’d at best have been looking after a male editor’s diary. Still, the sense that I missed out by arriving a few decades too late gnaws at me.

It’s a powerful feeling, one recognised by the men in power on both sides of the Atlantic. The most recent US and UK elections were rewritten by this creeping sentimentality toward a past most voters never actually experienced. Boris Johnson won his sweeping majority having urged voters to ‘Take Back Control’, and quoting Churchill to invoke the spirit of the blitz during the 2016 EU referendum. This backward-looking vision of Britain’s future, described by AA Gill in 2016 as “snorting a line of the most pernicious and debilitating Little English drug, nostalgia”, reveals the poison of glamourising the past. We’re not so much looking back as refusing to look forward.

It plays on the same emotional triggers as a particular style of Facebook meme, which still does the rounds, asking users to, ‘Like if you remember playing in the street until dark and never had a mobile phone!’. This blinkered focus on the past conveniently omits the three day week and anxieties over nuclear war, pit closures or explicitly racist election campaigns. It’s a type of performative nostalgia, an image of Britain as some perfect past that never really existed. Sharing with your friends, you say loud and clear: ‘I don’t like how it looks now’.

This conflict between real nostalgia and performed nostalgia, like the stretched shadows which Reynolds found so unnerving, is essential to understanding why social media sites are making features out of it. These ‘memories’ give us excuses to share old holiday photos, under the guise of nostalgia, which acts as a conduit through which we can broadcast more ‘me’. The sets at FestiveFriends, like at the events put on by experiential film group Secret Cinema, are backgrounds in which we star, a place engineered to inspire nostalgia in us and the people who'll see our photos later.

For Facebook, Leaver believes the endgame of social media’s nostalgia fixation is the platform turning into a kind of Who Do You Think You Are? repository of all your past photographs and friend connections, something that was hinted at in 2011 when the site changed user’s profile feeds to make it easier to jump back in time. "Facebook realises that it's got an ageing audience and that to keep all the users, [nostalgia] is the stuff that works the best,” he says. “I've got this theory that in 50 years, Facebook will turn into a genealogy service that sells you back your family memories.”

These dopamine hits of happy memories are the anaesthetic that tech offers to dull all the misery it serves up. As well as baiting us with the past through suggested memories on social media, technology has driven us to find places where we can unplug from the bombardment of bad news. A few hours spent watching Friends is a warm shelter from the spring and pop of pulling down your Instagram feed one more time. When everything feels uncertain, knowing that everything’s going to end with six friends staying friends is like cultural Xanax.

You can know that, but you can never really be immune. On the way home from work recently I saw an advert for a Human Traffic Live, an event based on a twenty-year-old film about the first blooms of club culture, in which people my age attempted escape their anxiety-ridden lives. The poster romanticised rave culture, promising it could transport you back to when clubs were better (ironically enough, the film contains a scene where two clubbers, high on ecstasy, reel off all the great nights that they used to attend and how the club they're in now doesn't compare). I was eight when the film was released, and yet I looked at the photos of people stood in a warehouse, arms held aloft – not one clutching a mobile phone – and longed to go back to somewhere I’d never been.